Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute in Australia make discovery which may change the future of heart attack treatment

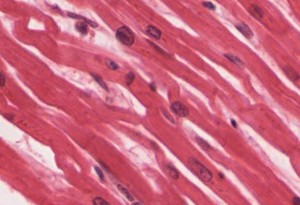

Most heart attack sufferers sustain some level of permanent damage to their heart muscle following a cardiac event. Heart attacks result when a blockage occurs in a vein leading to the heart, instantly causing muscle cells of the heart called cardiomyocytes to start dying. Unlike blood, hair and skin cells, the human heart does not know how to regenerate itself, and the damage is permanent. This may not be the case for much longer, however. Scientists from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and the Victor Chang Institute in Australia have discovered a way to stimulate heart muscle cells to regenerate by as much as 45 percent.

Capable of regenerating everything from a lost fin to a heart, researchers have long looked at the salamander and zebrafish with great interest in understanding the mechanism which makes them capable of heart regeneration. Unlike these unique creatures, the human heart’s ability to regenerate cells is controlled by the hormone neuregulin, which is blunted in infants about a week after birth, ceasing cardiomyocyte regeneration permanently.

According to Prof. Richard Harvey of the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute, “One thing they do is send their cardiomyocytes, or muscle cells, into a dormant state, which they then come out of to go into a proliferative state, which means they start dividing rapidly and replacing lost cardiomyocytes.”

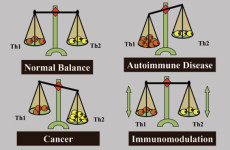

‘There are various theories why the human heart cannot do that, one being that our more sophisticated immune system has come at a cost, and because human cardiomyocytes are in a deeper state of quiescence, that has made it very difficult to stimulate them to divide’, Harvey told The Guardian.

However, recent research on mice has proven positive, showing that, at least in rodents, the regenerative barrier is indeed cross-able. By stimulating a neuregulin hormone pathway in the heart following a heart attack, the heart muscle cells divided, successfully recovering most of the heart muscle tissue in the studied mice.

“This is such a significant finding that it will harness research activities in many labs around the world, and there will be much more attention now on how this neuregulin-response could be maximised,” Harvey said.

The dream is that one day we will be able to regenerate heart tissue, much like a salamander can regrow a limb if it is bitten off by a predator. Just imagine if the heart could learn to regrow and heal itself.

“We will now examine what else we can use, other than genes, to activate that pathway, and it could be that there are already drugs out there, used for other conditions and regarded as safe, that can trigger this response in humans.” Prof. Harvey projected that scientists should be able to determine whether or not these results are replicable in humans within five years of continued research.

“The dream is that one day we will be able to regenerate heart tissue, much like a salamander can regrow a limb if it is bitten off by a predator. Just imagine if the heart could learn to regrow and heal itself. That would be the ultimate prize,” Harvey said in a statement from the researchers.

The research, conducted at the Weizmann Institute of Science in collaboration with the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute, was published in Nature Cell Biology.